Opening hours: every first Sunday from 2-5 pm and on request

The Museum auf der Hardt opens on Sunday, 7 December 2025.

About 25 visitors spent an entertaining evening on Thursday in the Museum auf der Hardt. The Archives and Museum Foundation of the UEM had invited to a lecture on music as part of its special exhibition Music by Notes - The Importance of Music in Missionary Work.

Prof Anna Maria Busse Berger, Distinguished Professor of Music at the University of California and author of the book The Search for Medieval Music in Africa and Germany, 1891-1961. Scholars, Singers, Missionaries, spoke about the African music researcher Nicholas Ballanta and the handling of music in the Bethel Mission. The audience learned a great deal about music techniques, challenges, and how missionaries dealt with local music.

Around the lecture, there was an opportunity to view the special exhibition and engage in conversation over a glass of wine.

From August 1 to 2, 2023, Namibian and German descendants of the missionary family Kleinschmidt were guests at the Archive and Museum Foundation of the UEM. Manda /Uiras, Otto /Uirab from Fransfontein, Ursula Trüper and other family members researched the historical holdings and visited both the written and pictorial archives and the museum on the Hardt to learn about the lives of their common ancestors - the missionary Franz Heinrich Kleinschmidt, who was sent by the Rhenish Missionary Society to what was then Groß Namaland as early as the 1840s - and his family. The letters of the missionary Rautanen - Franz Heinrich Kleinschmidt's son-in-law - who was sent by the Finish Mission, as well as numerous station files of various historical mission stations (including Rehoboth, Otjimbingue, Fransfontain) were also consulted.

They also investigated to what extent the history of the Swartbooi from Rehoboth to Otjimbingue, Ameib and finally Fransfontein can be traced in the mission files. The visit yielded numerous clues, points of contact, and questions for further research into their family history.

Inspiring experiences and exciting events await visitors in the first half of 2025: the new programme brochure of the Bergische Museums Network is here! It contains a selection of the best events organised by the member museums, including adventure tours, hands-on activities, lectures, museum festivals and much more.

Special highlights are the numerous co-operative events in which two or more museums work together. For example, the Museum auf der Hardt of the Archives and Museum Foundation of UEM, together with the Deutsches Schloss- und Beschlägemuseum in Velbert, the LVR-Freilichtmuseum Lindlar and the Museum and Forum Schloss Homburg will be showing ‘Kistchen & Kästchen’, in which ‘secrets & delights’ can be stored. Exhibits from the four collections, from different eras and continents will be on display in all four museums.

The exhibition ‘Contemporary Art, Culture and Resistance in West Papua (Indonesia)’ will also continue to be on display at the Museum auf der Hardt this half-year and will feature an event highlight in the current brochure: A panel discussion with, among others, Dicky Takndare, a member of the art collective Udeido, on 27 March 2025. The event is being held in cooperation with the West Papua Network.

The new programme brochure is available in the participating museums and is also available online on the joint website at www.bergischemuseen.de. There you will also find the comprehensive brochure in which all 28 member museums are presented.

Special thanks go to the Ministry of Culture and Science of the Region of North Rhine-Westphalia, the Regional Culture Programme NRW, the Mettmann district, the Rheinisch-Bergisch district, the Oberbergisch district and the cities of Wuppertal, Remscheid and Leverkusen, whose support makes the network's work possible.

With this topic, we are guests at the current special exhibition Land - Women - Work in the Weimar Republic at the LVR Open-Air Museum in Lindlar

from July 5 to September 30, 2024.

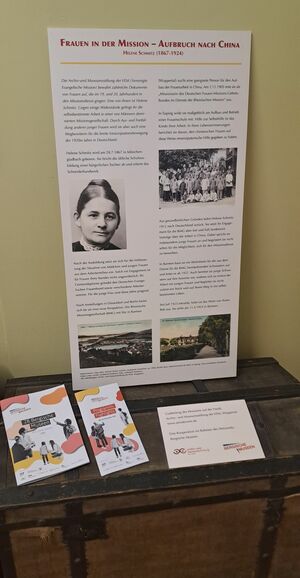

She paved the way for the emancipation of women during the Weimar Republic. As early as the time of the German Empire, Helene Schmitz was involved in Christian missionary associations for the education and training of young women from working-class backgrounds and gave them new, self-determined prospects in life. She then traveled to China for the Rhenish Missionary Society.

Find out more about the story of a committed and energetic woman in our guest contribution with our cooperation partner in Lindlar. This is a cooperation within the framework of the Bergische Museum Network (Netzwerk Bergische Museen).

The picture shows the first page of the instructions written in 1829 by the Rhenish Missionary Society (RMS) for its first 4 missionaries sent out on June 30, 1829. After a voyage lasting over three months, they finally landed in the South African Cape on October 7, 1829. After a period of exploration with and at the London Mission Society, the Rhenish missionaries founded their first mission station in the Cape, Wupperthal, on January 1, 1830. The actual work could now begin, but what did it actually consist of and what tasks did the mission intend for its "emissaries"? Their instructions shed light on this.

Even though the Mission was convinced that "the Holy Spirit is a better guide than all human instructions", the RMG Board nevertheless saw it as its "duty to give more detailed instructions about some parts of her future work [...]". These instructions extend over 7 paragraphs, the titles of which are as follows: "§1 Purpose of the mission, §2 General instructions for blessed missionary effectiveness, §3 Special instructions for our messengers, §4 The church of God among the Gentiles, §5 Extra-official activities, §6 Relationship of the brothers to each other, §7 Relationship of the missionary brothers to our committee."

The concern and self-image of the RMG was to spread the Gospel, so that the basic instructions for action also emphasized the need to learn the local languages. For example, point 4 "Dealing with the Gentiles" of paragraph 3 states: "Above all, endeavor to learn their language thoroughly as soon as possible. They will be glad to be able to teach you something, and this will create a bond between them and you." Learning the language is taken up again in paragraph 4 "The church of God among the Gentiles": "As soon as you can, take turns to hold services in the local language."

Indonesia, Nias, 2nd half 20th c.

This 32 cm long and 34 cm high architectural model is a detailed representation of a type of residential house that was typical of the extreme south of the island of Nias. Although the model was largely made of machined industrial wood in a simple, sturdy construction, it nevertheless shows the external features important for this traditional type of house.

Houses like these always stood in the settlements in an association of several dozen to more than a hundred buildings. As a rule, they were lined up close together to the left and right of the stone-paved street and the central square. The long side of the house shown in the picture gives a good impression of the hipped roof, high rising and at an acute angle, with the characteristic hatches that, when opened, let air and light into the interior and could be used in this way similar to a dormer.

From this perspective, however, it is not the front of the house which is shown. Rather, this is formed by the narrow side of the building, which is on the right from the viewer's perspective here. It is this side that faces the street and is distinguished by the characteristically curved, massive ground sills of the construction. The sleepers, in turn, rest on the massive pillars made of massive tree trunks, which were sunk vertically into the ground for this purpose. The side of the house seen here, on the other hand, usually comes very close to the wall of the neighboring house, which is usually more or less identical in construction. In this way, the houses join together to form a compact row along the street.

For the missionaries of the Rhenish Mission Society, who came to the region at the end of the 19th century, these unique architectural ensembles probably gave them the impression of being in an urban area rather than in a village. This impression was also supported by the complex social structure and the differentiated division of labor in the communities in this part of the island.

The model is one of 53 other house models from a private collection bequeathed to the archives and museum foundation of the UEM. They all represent traditional house types common in the many different parts of Indonesia, from Sumatra Island in the west to West Papua in the east of the island nation. Models of this type are very popular as souvenirs and are made and offered for sale in many places for this purpose.

The objects of the extensive collection had its owner during his stays in the country over many years either acquired, or he endeavored - where no direct offer was available - a commissioned production of a model of the respective local or regional type of construction.

"We are pleased to announce the publication of the long-awaited General Mission Atlas to our readers today."

With these introductory words, the Rhenish Mission announced the new work in its monthly report from 1867.

Background:

Between 1867 and 1871, the Gotha publishing house Justus Perthes published the General Mission Atlas, one of the few missionary cartographic works of the 19th century that was not solely dedicated to the missionary fields of a single denomination or even just a single missionary society, but also took into account not only the Protestant missionary areas but also those of the Catholic and Orthodox churches as well as the spread of non-Christian religions.

Admittedly, it is clear from the work that it was written by a Protestant theologian, as the focus is clearly on the fields of activity of Protestant missionaries. Originally, Reinhold Grundemann had not intended to compile such a general atlas, but rather to continue the series of Protestant missionary atlases.

Admittedly, you can tell that the work was written by a Protestant theologian, as the focus is clearly on the fields of activity of Protestant missionaries. Originally, Reinhold Grundemann had not intended to compile such a general atlas, but rather to continue the series of Protestant missionary atlases.

After many years of negotiations with the management of the Perthes publishing house, Grundemann moved to Gotha in 1865 and began work. Of particular importance here was the direct contact with the missionary societies, which Grundemann had already cultivated before his time in Gotha, but also far beyond that through various travel activities at home and abroad. Grundemann's networking work was of such enormous importance precisely because it not only enabled him to maintain contact with those potentially interested in his work and thus ultimately the future purchasers of the mission atlas, but above all because he also used this network to obtain the information required to compile the work.

In addition, some missionaries also provided further information, which they sent to Grundemann or persons associated with him in the form of descriptions and their own cartographic sketches of the mission area or a combination of both. This material, which unfortunately only survived to a very limited extent and usually for the period after the completion of the work on the mission atlas, was probably the most important source for Grundemann's work for one or other mission area, as these sketches made it possible to provide much more detailed information about the geographical features of individual regions or even exact positional data.

In addition to this first-hand information from missionary circles, Grundemann was also able to draw on a whole range of previously published sources. In addition to existing geographical and ethnographic works, many of which were also products of the Perthes publishing house, these included in particular the journals and annual reports of individual missionary societies.

Due to his close relationships with the missionary societies, it can be assumed that Grundemann was also able to draw on this material, at least in part, when compiling his General Missionary Atlas.

Despite various difficulties, Grundemann was able to draw on a wealth of material on which to prepare the publication of the mission atlas. Even though he himself must have been so clumsy as a cartographer, the General Mission Atlas itself not only represents the "first standard work of German missionary literature", but also provides far-reaching insights into both the missionary cartographic work of the 19th century and the various aspects of the circulation of this geographical knowledge from the mission territories thanks to its well-documented genesis.

The current general boom in mission history and the associated interdisciplinary research into missions, which is also increasingly approaching the subject from a history of knowledge perspective, gives reason to hope that the significance of missionary cartographic work for the opening up and discovery of the world in the 19th century will once again become the focus of academic research in the coming years.

Abridged reproduction of the article by:

René Smolarski: Reinhold Grundemann's Allgemeiner Missionsatlas und seine Quellen, in: ProMissKa, January 27, 2016, URL: http://promisska.hypotheses.org/42

Tanzania, end of 19th or early 20 th Century

"Yisa nkajilinwa na chala" is an old proverb of the Shambaa in the mountains of the Usambara region in northeastern Tanzania. At least that is how the missionaries of the Bethel Mission Ernst Johanssen and Paul Döring document it in their 1915 publication "Das Leben der Shambala beleuchtet durch ihre Sprichwörter".

The two translate the saying somewhat awkwardly, but probably very aptly: "With the finger (pointing only where to plow,) the fallow land is not plowed over." In other words, the reference here is to the fact that the work does not do itself, one must rather - and in relation to the current object of the month also quite proverbially - take the hoe into one's own hands in order to cultivate one's field.

It is striking that in the first chapter of their collection of proverbs, Johanssen and Döring examined "occupational life" with regard to idioms used there and here again first dealt with agriculture. This entry seems obvious, however, since agriculture was the most important livelihood for the population in the region when the first missionaries arrived there at the end of the 19th century. Livestock, handicrafts and (barter) trade were also practiced, but were secondary to agriculture. Accordingly, there are many phrases that, with the help of linguistic images from arable farming, refer to general practical aspects of life as well as ethical aspects with regard to individuals and their living together in the community.

Even today, the cultivation of corn, bananas, beans and other crops in the small-scale cultivated region makes an important contribution to (self-)sustenance in the households of the rural population. Cultivation was and still is labor-intensive on the slopes of the mountains. The use of machinery makes only very limited sense, either technically or in terms of the capital outlay required for such cultivation. Thus, even today, farming implements similar to the one shown here are the tools of choice for tilling the soil.

A missionary or a missionary sister was sent out to introduce or further spread Christianity in the yet-to-be-created or already existing mission territory. This was desirable in the mind of the sending organizations - the missionary societies and religious congregations - in all those regions of the world whose populations had previously had little or no contact with the Christian religion.

The idea behind the concept of sending therefore necessarily involved the willingness of missionaries to embark on a journey to the people to whom their mission referred. This necessarily involved traveling great distances, sometimes several thousand miles, across oceans, on roads, tracks or trails, and occasionally on river trips. Travel was time-consuming, often associated with great physical and psychological strain, and not infrequently with danger to life and limb.

But it was not only German missionaries who were sent from Barmen and Bethel to Africa, Asia, Oceania and America by the RMG and Bethel Mission in the following decades. Also early on, men and women from the mission areas also embarked on the reverse journey. They were usually members of the newly emerging mission churches, and some felt called to become missionaries themselves. In Europe they were trained at the seminaries of the missionary societies. The first of these trips took place as early as the 1850s, but without being able to sustainably train candidates from South Africa for the profession. Another example is Uerieta Kazahendike, a young woman from what is now Namibia. In 1860, she accompanied the family of the missionary Carl Hugo Hahn to Gütersloh in Westphalia to, among other things, proofread the translation of the Bible into the Herero language. A few years later, other young men from Asia made their way to Germany to be trained for missionary service.

Far more than 2,000 men and women set out from their homelands over the past nearly 200 years to the present for the two historic mission societies and their successor organization, the United Evangelical Mission (UEM), to begin their service or training "far away." With them traveled ideas, things, prejudices, insights and attitudes toward people from the respective other cultural context. These attitudes were often subject to lasting change, not least during the journey and in contact with the people and their own culture.

The development from traveling on foot, by horse and camel or with other beasts of burden, as well as from sailboats and rowboats to modern steamers and motorboats, via the historic railroad to modern express trains, from carriages to automobiles and finally to small airplanes and jet planes, symbolizes the rapid mechanization of means of transportation that the people of the Mission also used in the last two centuries. Even the suspension railroad, which is firmly anchored in both the Barmen and Elberfeld cityscapes, underwent modernization and expansion during this time. Thus, even the experiences and impressions on the first trip and even before arriving at the actual destination become unforgettable moments that are enthusiastically described.

The present also poses new challenges for the work of the United Evangelical Mission (UEM), which was formed from the merger of RMG and Bethel Mission in 1971. These challenges are overcome with the help of the most modern travel medium - the Internet - to ensure close contact and barrier-free cooperation between today's partner churches.

Tanzania, 1990s

Like some of the objects presented in this series, the dustpan shown here belongs to the group of practical household appliances that are made from recycled material all over the world. As is so often the case, the starting material is tinplate from boxes that had a previous life as packaging material for consumer goods of various kinds. The object with its simple but functional design was manufactured in Tanzania. It is another example of the professionalism and creativity in the reuse of used materials, especially by craftsmen and artists on the African continent.

But the object also tells another story. It is evident from the past life of the rolled sheet that was used to make it. The imprint advertises the drug Nivaquine, better known in Germany as Resochin, an industrially produced active ingredient whose chemical compound is similar to quinine and thus the oldest known remedy against the disease malaria, which is widespread in the humid tropics. The endemic disease kills more than 600,000 people worldwide every year, with more than 95% of the deaths occurring on the African continent (593,470 in 2021, according to statistics from the World Health Organisation, WHO).

The dustpan - presumably not entirely unintentionally made in this way by the craftsman who created it - thus bears witness to one of the greatest challenges for African health systems, which is undoubtedly the medical treatment, but above all the prevention of malaria. For the promise to be read in big red letters in Kiswahili "hushinda malaria kabisa!" (Defeat(s) malaria completely!), the drug, which was also approved in Europe from the 1950s onwards, was ultimately unable to deliver. Many of the pathogens of today's malaria variants are now completely resistant to the active ingredient of the drug. The protection of the whole family - as suggested by the photo printed next to the slogan - is no longer possible today.

Although the situation in this regard was somewhat different a good 25 years ago, in addition to the medical efficacy of a medicine, the limited access to such medicines was then and is now a problem for large parts of the population. This can be the case both due to a lack of basic health care in rural areas or in crisis regions and/or due to people's lack of income to be able to afford pharmaceutical products of this kind. In this respect, the dustpan can also be seen correspondingly as a mirror of global socio-economic structures in which equal access to life-sustaining resources - not only in the medical field - continues to be denied to many people and especially in Africa.

If one reads "hushinda malaria kabisa!" against this background more as an appeal than as a promise - even if the manufacturer of the product probably did not understand it in this way in his advertising at the time - then the approaches to a solution may perhaps lie less in a purely medical solution than in a solution for society as a whole.

There is remarkably little to be found about watchmaking in Lwandai in the archival texts. One exception are the largely preserved annual financial statements of the businesses of the missionaries of the Bethel Mission in Usambara. Until 1930, these rigorously document the turnover and net profit of the watchmaking business, and even the turnover of individual months is listed in part. From 1933 onwards, however, this changes: the watchmaker's shop is "no longer given a separate account", but can only be found in the figures for the Duka (Kiswahili: Shop/Business/Operation), which also include the tailor's shop and the shoemaker's shop. The reason for this is obvious in view of the disastrous figures for watchmaking and the general situation in the 1933 business year: in 1930, a total of 404 watches, i.e. less than two per working day, were repaired with a net profit of only 106 sh. The businesses as a whole stood at a net profit of 603 sh in 1933, which corresponds to less than half the operating net profit of the surrounding years.

However, we can learn something about the Bethel Mission precisely because of the missing documents about the watchmaking. Contrary to the assurances that all "businesses [...] would have to support themselves in the course of time", the watchmaking workshop remained until the end. One was more than willing to overlook the economic insignificance because the goals were completely different: "In all these businesses [...] a small class of healing assistants, printers, typesetters, bookbinders, carpenters, watchmakers, tailors, shoemakers, scribes grows up in the individual employees in the quiet of laborious, patience-seeking small work. This educational work should not be overlooked in its importance for the social fabric of our people [here the christian community is meant]." This pathos reflects the protestant work ethic established by protagonists such as Luther and Calvin, which soon became secularized as part of bourgeois German national culture.

Likewise, the VEM's holistic understanding of mission is preformed in the work of Bethel Mission. By recruiting all kinds of German professionals (mostly from the church environment) to establish farms and hospitals in Tanzania, Bethel Mission created a thriving church complex that extended into everyday life. In contrast to what Habermas calls the "functional differentiation of social subsystems" in the West, a public significance of Christian religion opened up in Tanzania that was already disappearing in countries like Germany.

Embedded in these contexts (Protestantism, German national culture, holistic mission understanding and colonialist thinking), the Bethel Mission and with it a small watchmaker's shop in Lwandai had an impact.

Namibia, 19th or early 20 th Century

This simple and practical tool measures only a few centimetres. It is a piece of iron forged flat and tapering to one side. The tapered end is also ground into a sharp bevel.

In the collection inventory, the object is described as a razor, although in view of its probable handling, it can more accurately be described as a scraper or shaving knife. However, its use for shaving beard or hair cannot be assumed as certain. Wielded at a shallow angle between the thumb and angled index finger and against the grain of a hairline, a use for working on animal skins also appears to be a sensible purpose.

In any case, the blade is likely to have had some value in the household of its owner, as was the case with all objects forged from iron and especially blades. The processing of iron ore was laborious and required expertise and professionalism. For this reason, blacksmiths were valued by the population in southern Africa and their products were in demand.

For the cattle-keeping and partly nomadic societies, tools like this were practical in various ways. On the one hand, blades of this or similar types were indispensable for processing slaughtered livestock. On the other hand, such tools were small and comparatively light, so that they hardly burdened the household goods on seasonal migrations with the livestock.

Ovamboland, Namibia, around 1964

A !Kung boy plays on a music bow. It is fluted. The stick is moved back and forth over it. The string is held in the mouth, the tongue and the mouth move. The mouth is used to produce the sound. Fine tones are produced. The bow, the hunting instrument, can also be found in this variation for the stringing of existence.

The musical bow is a stringed instrument in which one or more strings are stretched between the ends of a flexible and curved string carrier. The string tension is generated by the bending force of the usually thin and long support rod. It belongs to the group of staff zithers. The special form of a musical bow without a sound box, in which the player's mouth is used to amplify and modulate the sound, is called a mouth bow.

Musical bows are or were widespread in large areas of Africa, Asia, Europe, and both American continents. Today, their main focus is in sub-Saharan Africa. Worldwide, the Khoisan have developed the greatest variety of musical bows in southwestern Africa.

The most commonly played hunting bow has a string loop that divides the string in the middle to create two low fundamental notes, the difference between which is about a whole tone. The bow is a little over a meter long, it is gripped in the center of the left hand and held at an angle to the lower left, away from the body. The player puts the upper end into his mouth so that the right cheek is pushed outward. By changing the position of the mouth, he can amplify several overtones. The shorter string section is closer to the mouth.

Alternating use as a hunting bow and a musical bow has survived among the ǃKung to this day. Another technique of the ǃKung to play the mouth bow is to take the back of the bow approximately in its middle to the mouth. The upper lip rests firmly on the bow stick, and with the lower lip the musician makes movements as if he were speaking. In doing so, he produces additional sounds of noise. The string consists of a twisted strip of animal skin that is wound tightly at the ends of the stick. The tuning loop is placed near the center of the bow. The player can selectively amplify a maximum of the sixth overtone of the lower fundamental and the fifth overtone of the higher fundamental via the two fundamental tones, which differ by a whole tone, by shaping the mouth accordingly.

(Source: Wikipedia: de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mundbogen)

China, 20th Century

Even those who do not play a musical instrument themselves and perhaps have little interest in music are familiar with the harmonica. Small and handy, it is the ideal instrument for the pocket and on the go. This makes it suitable for solo use almost anywhere and at any time. Yet it is a comparatively young instrument that was first manufactured and played in Europe in the first quarter of the 19th century using a (partially) mechanised manufacturing process.

It is usually less well known that the harmonica is merely a modified form of a much older musical instrument. The mouth organ sheng, which consists of eighteen bamboo tubes and a wooden wind box connected to them, has a history of about 3000 years in China. It is one of the oldest instruments documented in East Asia.

The sound is produced by blowing air through the mouthpiece and varied by the player's fingers alternately covering the holes in the bamboo tubes. However, a free-floating tongue inserted into each tube is responsible for the basic colouring of the tones, past which the blown-in air must flow.

It is this physical principle that has been adopted in the harmonica. However, this also applies to another instrument that not only implies a kinship in name, but was also the musical instrument of choice of European missionaries in the 19th and early 20th centuries when it came to their evangelising mission in Africa, Asia and Oceania: the harmonium.

This instrument is also a 'newcomer' compared to the Chinese mouth organ, which was only built for the first time in France in 1848. The physical-mechanical principle, however, is the same as that of the mouth organ, for the tone is produced by blowing in air, here by means of a foot-operated bellows, which then flows past reeds of different lengths. Only the control of the tone sequence is outsourced to a valve system connected to a keyboard. With the 'original principle' of the sheng, this part is done by changing the hole cover, similar to playing a flute. This, in turn, was the first aerophone from which man could not only elicit a sound by blowing into a tube, but also vary this tone through the active use of his fingers in many ways.

Missionary and locksmith Ewald Schildmann, first sent to Sidikalang, Sumatra, Indonesia, in 1937, describes in a 1956 report:

"Already some time ago I received an invitation from the Batak pastor from Doloksanggul to come to a church festival with my wind players. There I should also preach. I was especially happy about this invitation, because 18 years ago, when I came to Sumatra for the first time, I had started to learn the Batak language with the old missionary Quentmeier in Doloksanggul. At that time I had lived at the mission station for 4 months. Since then I had never been back to Doloksanggul ... What I could fit in my car in terms of wind instruments, horns and other luggage was stuffed into it ... After about five hours of driving I had happily steered my car with my wind instruments to the destination. We were in Doloksanggul. The others in the bus also arrived soon after us ... Of course, we had to blow some chorales immediately after the welcome. So also the other inhabitants of Doloksanggul heard that we had arrived ... After lunch we went to the big new church. It was lit with kerosene lamps, because there was no electric light in Doloksanggul. The church was full to bursting. It is very spacious and has about 1500 seats, at least that is how many are planned. There were no pews in the galleries yet, but there the youth were crowded together, shoulder to shoulder. It was the same down in the nave, in all the aisles, right outside the doors. I have never seen a church so crowded. This was probably because there was so much room for standing through the wide aisles and wide galleries. The congregation was singing and so were the choirs, some really well trained. A young natak pastor from the neighboring parish spoke before me. And then I gave my evangelistic sermon on the parable of the mustard seed ... It is always like a miracle that the Asians are still able to hear the word of God from the mouth of a white man. As I wrote above, only a few of the old people here still knew me. For these more than 2000 Batak I was a complete stranger, at first only a European, a white man... On these evangelization trips I really grow together with the individuals, because there they come out of themselves and ask. What more could a missionary want in his work than to be a preacher and pastor?

Picture: Part of the wind orchestra under the direction of missionary Schildmann, Doloksanggul 1956

Bali, Indonesia, 20th century

The majority of the population on Bali is Hindu. In the mythology of Hinduism, the world of demons and various spirit beings plays an important role. The traditions find their visible expression, for example, in the shadow play theater wayang kulit and in ritualized dances. While in the shadow play the mythical protagonists are embodied by corresponding hand puppets, in the dance performances it is the masks which - led by their actors - present episodes from the work of the mythical beings in fixed choreographies.

The most famous mask in the context of such a dance theater is barong kèkèt. It embodies the spirit being banaspati raja. Although banaspati raja in the form of barong must be understood as an apparently frightening demon, he nevertheless stands for the good, the positive element in Balinese mythology. This apparent contradiction becomes understandable when one considers the barong's function as a protective spirit and guardian of the souls of the deceased. His imposing, respectful appearance enables him to separate the spheres of the living and the deceased and to defend them against evil-desiring forces. Both are necessities to which attention must be paid in many religious traditions of South and East Asia.

It is equally important not to exclude the negative element, the evil-desiring powers and the spirit beings representing them. Rather, in the Balinese-Hindu understanding, ideally a balance between good and evil is always strived for. The struggle of both elements finds its expression in the masks and their guidance during the corresponding choreographies. Thus barong finds his adversary in rangda. She is an embodiment of the goddess of revenge durga, who can stand for the negative powers par excellence.

The barong mask seen here, with its red-colored face, large bulging eyes and imposing fangs, is indeed a typical representation. However, it is merely an imitation of the facial part of an original dance mask. In addition, such a mask usually includes a lower jaw that can be moved by means of a folding mechanism, a long tongue made of parchment or leather, a luxuriant hairstyle made of palm fiber tufts, and a voluminous costume that is worn by two players and brought to life by the dance in a joint choreography.

Only in this way can the mask become the lion-like creature that, after a long struggle, triumphs over its adversary rangda at the end of the dance. But the victory over evil will only last until a renewed challenge by rangda.

Drawing from 1935, Portrait Gottlieb Murangi

Born in 1900 in Switzerland, Liesel Hohl came to the Malche Bible House in 1924, where she was trained as a missionary teacher. In response to a request from the Rhenish Mission to take charge of the school in Grootfontein, Southwest Africa, she led the school from 1929 to 1948. In addition to school work, she was involved in children's services and evangelistic work. In the fall of 1948, Liesel Hohl returned to her native Switzerland, where she worked as a teacher in Basel until her retirement. Liesel Hohl passed away in 1983.

She particularly contributed her artistic abilities and drew a lot. Thus also Gottlieb Murangi, chief evangelist among the Herero.

Gottlieb Murangi, born in 1863, was active for the mission for 65 years. Baptized at the age of 10 in Otjikango, he taught school children and taught many a missionary the Herero language. In 1909 he was appointed by the government as a policeman before being employed as an itinerant evangelist by the Rhenish Mission from 1911. Missionary Christian Kühhirt, who worked with Gottlieb Murangi for many years, wrote about him in Windhoek in 1950: "Our co-workers are necessary to us not only because they should and must do the work for us, because we are not able to do it alone, they also have a fine, completely different visual language. And when they preach the Gospel to their fellow people, it is naturally much more impressive and lively than when a stranger does it ... He shared joys and sorrows not only with the church, but also with us missionaries. How he felt responsible for the missionary women when their husbands were away on farm trips, he prayed with them, he comforted them."

Gottlieb Murangi was a remarkable man who enriched and supported the work of the mission beyond all the challenges of the time. He passed away on May 31, 1948.

China, second half of 19th century or beginning of 20th century.

The resonance body of the 13-stringed instrument is covered with a plate made of tung wood, in which two sound holes covered by finely carved bone plates are embedded. The base of the resonance body and the cover made of dark brown lacquered wood serve as a case for the instrument. The bridge, originally very likely in the middle position, is no longer present. The same is true for the sticks for striking the strings as for the tuning tools. In instruments of this type, they were kept in a compartment located in the rectangular recess at the front.

The yangquin was not a genuinely Chinese instrument. It was not until the end of the Ming Dynasty (after 1644) that it was introduced from the Near East. While its old name "foreign zither" 洋琴 still refers to this, today it is also colloquially referred to as the butterfly zither 蝴蝶琴. This name refers to the "baroque" shape that the instrument acquired only from about the middle of the 19th century in China. It was based on the taste of the time and the formal style in the furniture industry of the Guandong Province in the south of the country at that time.

The yangquin shown here was made in southern China, in the city of Guangzhou (Canton). The affixed labels refer to a store on Hao Bin Street. The street was colloquially known as "Musical Instrument Street" because numerous musical instrument dealers and instrument workshops had set up shops there. The city on the Pearl River Delta was also frequently visited by RMG missionaries and missionary sisters, as it was the urban center of the Society's comparatively small mission area in the country. It is possible that the instrument was acquired during such a visit.

Furthermore, the zither is most likely a training instrument. This is indicated by the two slanted labels. The characters reproduce a traditional Chinese notation, according to which one can learn to play.

The instrument is currently on display in the special exhibition "Mission by Notes - The Importance of Music in Missionary Work" as part of the theme year "All in Connection" of the Bergische Museums Network. After the end of the exhibition, the object will be returned to the depot.

Letter from F. Schneider, Windhoek, Namibia to Missionary F. Harre in Wuppertal, October 12, 1965.

"Dear Missionary!

As an attachment I take the liberty to give you our first record with trombone music. Even though it did not turn out as we had imagined, this is due on the one hand to the fact that we have absolutely no suitable recording space and on the other hand, as far as the fineness of the blowing is concerned, the choir is still relatively young. Nevertheless, we hope that we can give you a little pleasure and ask you to point out the possibility of buying this record when you visit us. I could imagine that this would be gladly used as a gift, especially at Christmas. If we have appropriate addresses available, we will ship directly from here. Of course, we would also be happy to send you a number if you wish.

With warmest regards

Yours

Fritz Schneider"

Reply letter

Letter from F. Harre (Bild + Film Dept. in Wuppertal) to F. Schneider in Windhoek dated 5.11.1965.

"Dear Mr. Schneider!

Thank you very much for sending me the first record with trombone music. I have listened to it with great interest and must tell you that the trombone choir is already accomplishing all kinds of things. I will gladly refer to this record at every opportunity. Unfortunately, you did not tell me how much this record costs. This information is important if I am to recommend the record.

I understand that you may be coming here with a small trombone choir. I believe that if you then play in churches, you will have the strongest sale of this record.

This record would be even more interesting if the trombone choir played not only German melodies and German compositions, but African ones. But I don't know if something like that already exists. I found composers in South Africa among the Basutho who composed themselves ... I wonder if you have something like that already? That would be good if you paid attention to it, if something like that can be found, that we are very interested in it.

I have some records from the Catholic Mission in Congo, where African music has been processed. These records are very interesting and are of course more in demand in our country than when a trombone choir in Africa plays European melodies and compositions.

In the hope that you and your wife are still doing well, I send you my warmest regards.

Yours

Fritz Harre

Picture: The technicians, missionary and sister, at work in the recording room during the 125th anniversary of the Rhenish Mission, already an independent Evangelical Lutheran Church, Okahandja, Namibia, August 1967.

Papua New Guinea

20th century

The body of this drum was made of light wood in one piece and has elaborate relief carving and two handles. In addition, it is painted in many colors following the relief courses. The membrane over the soundbox is made of the skin of a monitor lizard.

The use of this type of drum has a long tradition in the eastern part of New Guinea, now Papua New Guinea, and drums of this type are still made and used there today. This is true both for use in religious rituals and in the context of musical performances and celebrations of national scale.

The drum's construction is suitably adapted to its preferred use. Since musical performances are usually always accompanied by danced choreographies, the very light body, equipped with the two handles, allows the drum to be used in the literal sense of the word. It also allows the musician and dancer to perform faster and more complex movements during the performance.

Variants of this type of instrument are known in many regions of New Guinea. Also in one of the UEM member churches in the highlands of West Papua, similar drums are often used in church services and during other festivities. In this way, the rich cultural tradition of the people of the region can be linked to the Christian religion, which was first spread to the highlands of West Papua in the 1960s by missionaries of the Rhenish Mission Society.

The drum will be on display in our upcoming special exhibition "Mission by Notes - The Importance of Music in Missionary Work" as part of the third theme year of the Bergisches Museum Network.

Ferdinand Genähr was 24 years old when he began missionary work for the Rhenish Mission in the city of Taiping, China. Genähr was a trained bookbinder and completed his training at the RMG seminary from 1843-1846. He died in Hoam at the age of only 41.

Genähr's beginnings in Taiping

Missionaries Genähr and Köster were in Victoria, now the Central district of Hong Kong, to learn the language and make exploratory trips into the surrounding countryside. Missionary Köster returned ill from one of these trips and soon died in Hong Kong. Missionary Genähr left Victoria and traveled to Taiping in late November 1848, then more than two days' sea voyage away from Hong Kong.

The reports of the Rhenish Mission state:

"In one day one can reach probably 30 villages from the city, which get all their needs from here; almost every house is a store; also there are factories etc… In the first 5 weeks he [Genähr] had a lot to do with healing all kinds of sick people ... the two preachers [who accompanied him and were placed at his side by the Chinese association] went into the city and its surroundings to preach in the houses etc ... He [Genähr] also went out with his preachers."

The Chinese preachers were taught by him for at least 2 months, and then preached in the surrounding countryside. The first person Ferdinand Genähr baptized was Ho, a medical doctor.

About the Chinese language he wrote: "You [Genähr himself] will not learn Chinese! I believe that under the mighty assistance of the Lord, half of this mountain has been climbed, by which I do not mean that the half yet to be climbed will make me a master of the Chinese language, but I hope that I will then be able to preach an intelligible sermon and converse about religious subjects in the popular language."

Ferdinand Genähr was followed by numerous missionaries and sisters in Taiping.

Namibia, 20th century

A little over a year ago, a device was presented here that was characterized by its simplicity, but above all by its impressive efficiency for its intended use. It was a barked branch about 55 centimeters long, sharpened at one end by a precise cut and used as a digging stick. The users of these devices were the women of the San and thus members of a population group that inhabited all of southern Africa before the arrival of Africans from more northerly parts of the continent and the first Europeans. There they originally led a life based on a nomadic hunting and gathering economy.

The container seen here, with its comparable attributes of simplicity and efficiency, is another example of the often quite reduced material culture that is inherent in all societies that lead a largely nomadic life, beyond economic bases such as agriculture and livestock.

The starting product - an ostrich egg - only needs to be selectively opened on the narrower 'head side' and the whisking and emptying of its content to produce the corresponding container. The whisked content can be consumed directly. However, in contrast to the women's digging stick, the container itself is only used stationary and is also used by the men for their tasks in the traditionally defined division of labor in San society. It is filled with fresh water, closed with a clay plug and buried in the ground. It serves as a liquid depot. Several of these small depots are strategically placed along the commonly used hunting and migratory routes so that drinking water can be withdrawn when needed. Under the extreme climatic conditions in the steppes and semi-deserts of southern Africa, the establishment of such depots represents an adaptation to the environmental conditions, which may be essential for survival.

It is not necessary to dig up the egg shells to extract the liquid. Rather, their contents are removed with a suction tube after removing the plug. This method, in turn, makes unnecessary handling of the comparatively robust container superfluous, allows it to be refilled later and keeps any remaining water fresh by storing it underground.

Last but not least, broken ostrich egg shells are still used by the San in the processing chains for natural products. The shell fragments are the raw material for crafting jewelry and appliqués for clothing.

The flying foxes (Pteropodidae) are a family of mammals in the order of bats and the largest species of bat. They are primarily crepuscular or nocturnal. When foraging, they often travel long distances, and during the day they sleep hanging upside down. Unlike bats, fruit bats are often found hanging from trees in exposed locations.

Another difference from bats is their lack of echolocation. Fruit bats have well-developed eyes and an excellent sense of smell. Due to the warm climate in their range, they do not hibernate. Flying foxes feed on plants.

Idjivi Island, where the flying fox colony lives, is located in southern Lake Kivu, Congo. It is also called Flying Fox Island or Napoleon Island (because of the silhouette) and is a popular tourist destination.

The picture is from a Bethel Mission convolute, no further explanation of the year it was taken or who took it is available.

Bethel Mission began its activities on the island in 1909 as the first European missionary society.

Tanzania

19th or early 20th c.

Wooden mortars or pestle troughs of this type were probably one of the most widespread household utensils in sub-Saharan Africa, and some are still in use today for self-sufficiency in rural areas. In addition, the crushing of plant parts or the processing of harvested crops into edible food in this form is very early in human history and globally verifiable. It is therefore one of the oldest cultural techniques in the world.

Its equivalent is found in a smaller form and made of materials such as marble, other rocks with comparable physical properties, porcelain, bronze or iron as an indispensable aid in pharmacy or for the preparation of fine spice mixtures in the kitchen.

The mortars of the type presented here are likely to have been used mainly for processing millet, local tubers, but also maize, which was later increasingly cultivated in sufficiently humid areas. The flour thus obtained from the starch-rich seeds and tubers is then usually processed on the stove or stove into a porridge, which is eaten as a main meal or as a side dish with sauces, meat or vegetables.

The physically hard work with the mortar was and is done by women. The pounding is done by continuously dropping the pestle into the mortar. The physical effect on the material to be crushed does not result from active pounding, but rather from the weight of the pestle as it is dropped or from the release of energy when it is struck after the downward movement.

Eduard Fries was director of the Rhenish Mission from 1921 to 1923. More than 100 years ago, at the beginning of 1922, he wrote in the reports of the Rhenish Mission:

"A "sursum corda" to the New Year!

No matter how hard we have to suffer under the hardships of the present time, all earthly distress brings us a great blessing: More impressively and more deeply than usual, the ever-valid truth of the New Testament Word ... becomes apparent to us, because a similar situation provides the clearest commentary on it. With how much more mature understanding we missionaries, for example, can read and take to heart after the experiences of the last years what Paul speaks of glory in 2 Corinthians ... From the "we are afraid, but we do not despair" in the 4th chapter, to the similar word "as the chastened and yet not slain" in the 6th chapter: What a wealth of inexhaustible refreshment just for us! ...

Some time ago, in a Reformed congregation dating back to the old Huguenot times, I became acquainted with a valuable church seal, which shows us in relief a palm tree, with a bent trunk under the heavy weight of its fruit, yet finally growing straight up to heaven; below it the inscription "curvata resurgo", i.e. "Bowed down I rise up". This is the courageous "nevertheless" of a professional attitude that recognizes and acknowledges in all the blows of fate ... the divinely wise education, and thus manages to rejoice gratefully even in a time when it passes through heavy darkness, instead of merely lamenting ...

With many I am confident that this way of our generation has not yet become a legend, but will prove itself in the face of an unprecedented and unjustified oppression. And if anyone is obliged to guard and increase such inner elasticity, it is the Christian who can lift up hand and heart in faith, also in this coming New Year's Eve, with the humble and at the same time courageous confession: "curvata resurgo" ...

We may sing again in the New Year: "Go your ways in peace, with you the great God's grace and his holy angels' power"; and it is thus preached aloud to all of us by the course of events, which we cannot make: "You dear Rhenish mission may stir your wings again ... let not the elasticity of faith be atrophied, then you may confidently create still further; in the midst of all the hustle and bustle and under heavy burden I lift you up!". With a trembling soul and a wavering mood, we do not comply with these instructions of God; and when we walk bent over, with our gaze to the earth, we do not become aware of His beckoning. Therefore: sursu "m corda!", i.e. "hands up and hearts lifted high", that a single note of frank confession may express our confidence for the new year: "curvata resurgo".

We wish you health, elasticity in faith, confidence and God's blessing for the year 2023.

Tanzania, Kagera Region

20th century

Depending on the quality, bark bast fabric, elaborately produced by beating, fulling and constantly moistening, was widespread in western Tanzania and in the neighboring regions of East and Central Africa. It was and still is used as a versatile everyday product – for example for the production of clothes and blankets or as packaging material – as well as in a religious context. In some population groups in East Africa, the fabric accompanied people throughout their lives: newborns were laid on a piece of bark bast, strips of bark bast could be laid out in the living room like a carpet, the deceased were wrapped in it for burial. With the Baganda in Uganda it was and is a sign of royal dignity. Today the material has largely been replaced by the cotton fabrics introduced in the century before last and later also increasingly by synthetic fibres.

The panels, painted with Bible verses, are set against a backdrop of a craft revival of the ancient technique. In a way, they combine social and religious symbolism that existed before the missionary work with the Christian-European tradition and usage of the house blessing, which is intended to express the piety of the residents of the house as wall decorations.

The sign board seen here is framed with strands of raffia that are alternately colored turquoise and left in their natural state. The bible verse painted in black paint and accented with white paint translates from Swahili to "May the grace of the Lord be with you".

A story from the “Kleine Missionfreund”, a magazine of the Rhenish Mission for children, by Mrs. Martha Pönnighaus, 1926:

"When it wants to be Christmas with you, dear children, the days are short and the dark nights are long; the sun shines only a little and does not rise high in the sky and no right power ... It shines in time all the more on the other side of the earth. And on this other side, that is where we live. When it gets cold with you in November, it gets quite hot with us. And when it's the darkest day for you, just before Christmas, the sun shines the longest here, and you don't stop sweating the whole day...

They [the children] also want to be at the Christmas party, they want to see the Christmas tree and they want to get presents! And every year the Christ Child has brought something to the school children! There are no apples. But a piece of bread, which they rarely get, and a small colorful bag to wear around their necks... The girls were allowed to help with the sewing of the bags. What a life in the sewing room! Each rag was different in color! ...

But now I wanted to tell about Christmas. Finally the day had come. In the evening ½ 8 o'clock should be the celebration ... There, ¼ after 7 o'clock, the bell rang! A storm of children, a jubilant chant with shouts of joy whirled past the house to the school! ... Another ¼ hour they have to control themselves and wait. Only then the door is opened ... We have to be content with an imitation, small Christmas tree, decorated with lots of tinsel and candles. It is not obvious that it did not grow outside in the forest... How loudly and clearly the children recite their promises and the Christmas story! ... Then the missionary gives a German speech. Each sentence is translated into both languages by a black man who can interpret. He really knows something! He also knows English and Dutch. Now come the gifts ... Each child is called and comes to the front, receives his bag from the hand of the missionary's wife and bread from the hand of the black teacher ... After the final song, everyone leaves the room in order. But outside, the joy can no longer be mastered ... But joy must be allowed to become loud, especially among children, so the grown-ups gladly allow it and they rejoice with them."

The picture shows the church of Hoachanas at Christmas. Hoachanas is located about 200 kilometers from Windhoek.

Botswana, 20th century

Simple - but very functional: This could be the headline for our current object of the month. The ring, made of available and suitable plant fibers or synthetically produced cord, was and is used in many parts of the world and especially in Africa as a carrying device for loads of all kinds and different weights.

The diameter can vary from model to model and is ideally adapted to the shape and base circumference of the container used for transporting the load or the nature of the load itself.

In addition to the transport of crops or goods for sale, in many rural areas, but also in so-called informal settlements on the outskirts or in the big cities, without a developed drinking water supply, it is above all water that often has to be transported on foot, often over long distances. The heavy clay jug, to the base of which the ring is or was best fitted, has almost completely become obsolete. It has been increasingly replaced by much lighter plastic containers, which may also be easier to seal. In some regions, aluminum or other light metal containers are also used as an alternative.

The load is carried by placing the ring on the head and adjusting it on the ring so that the load can be balanced when walking upright and carried with as little loss as possible. It should be noted that above a certain weight it is no longer possible to lift the load on your head alone and with your own strength. As far as the transport of water is concerned, the activity is therefore easier and more efficient to be done in a group, which is often the case.

It is almost exclusively women and girls whose everyday work involves these physically difficult tasks. Balancing the load also requires a great deal of skill. Again, especially when it comes to the transport of drinking water, there are often several kilometers to be covered through sometimes difficult terrain. The physical strain is high, even if carrying a weight aligned in the extension of the upright, i.e. vertical body axis is gentler compared to other types of load carrying, which put more strain on the arms, shoulders and spine. It is true that the transport of heavier loads can often be better managed with aids such as bicycles, carts or the use of beasts of burden. However, purchasing and maintaining such aids is always an additional investment that many households cannot afford.

At the mission station in Mlalo/Hohenfriedeberg, Tanzania, numerous printed products were produced for the mission. Mission Inspector Walter Trittelvitz wrote in 1911: "How could it be otherwise than that the translation of the Holy Scriptures was soon started? The Gospel of Markus was the first ... Other parts of the New Testament and Bible stories of the Old Testament in various editions followed, until in 1908 the whole New Testament in the excellent translation by Missionary Roehl could be brought to print ... and now Elisa Tschagusa, a young Shambala Christian, typed the manuscript of the New Testament ready for printing."

Elisa Tschagusa was a teacher, taught music, directed choirs, and was also a preacher.

"In all of this, the great difficulty of getting a book that is written in Africa and is to be used in Africa printed in Germany became apparent. Because often enough there was no one in Germany who could read the proofs. The proof sheets had to travel back and forth between Germany and Africa, and everyone can imagine what a tremendous delay the printing suffered as a result. That is why we have already turned to the communal printing house in Tanga for the last printings, so that it can complete the printing ... We must take the step that many a missionary society has taken before us, and establish our own missionary printing house in Usambara ... A young Christian book printer, who had already registered with us for missionary service some time ago, has been chosen as the manager of this printing house; he is currently working here in Bethel near Bielefeld, in order to receive the last necessary training."

A short time later, through donations, a printing press could be set up in Lwandai.

The picture shows Elisa Tschagusa at the typewriter on which he is typing the translation of the Bible for printing.

Travel oven

China, 19th or early 20th century

Small kilns made of clay were a useful travel utensil in China. They made it possible to prepare tea on the go with minimal effort or were only used to heat water. The production of this everyday object made of fired clay required comparatively little effort; the device itself is an efficient travel companion.

Among other things, it could be used on the numerous freight and passenger vessels that plied the great Chinese rivers. On their travels in the former mission area at the mouth of the Pearl River, located between Hong Kong and Quangzhou (Canton), Rhenish missionaries may have used such devices from time to time. Society missionaries were active in the area beginning in 1847. The stoves could also be stowed in the luggage of a pack animal or in one of the typical single-axle wagons used for overland travel.

Even today, the preparation or provision of heated drinking water on longer trips is a standard in the country.

The object can be seen in the permanent exhibition of the Museum auf der Hardt.

The Daughters' Boarding School in Stellenbosch, South Africa

After 30 years of activity, a second generation of missionary families had grown up in South Africa. In 1858, there were 49 missionary daughters under the age of 20 among them.

The deputation of the Rhenish Mission in Germany decided to establish a boarding school for daughters in Stellenbosch. The boarding school was also to be open to other girls and thus the language of instruction was to be English. The teachers selected in Germany, Julie Pieper and Bertha Voigt, together with the missionaries Lückhoff and Terlinden, constituted the board of directors.

Instructions were drawn up which, in addition to general decisions for the boarding school, also defined the tasks of the teachers, the board of trustees, and furthermore the board of directors.

"On May 1, 1860, a ... boarding school opened in Stellenbosch, a house of education for the daughters of our African missionaries."

In 1880, 130 students and over 70 boarders attended the Daughters' Boarding School, including 7 missionary daughters. The boarding school was self-supporting through school fees and boarding costs, and financial support from the mission in Germany was no longer necessary.

Stellenbosch became the center for the education and training of the daughters of the Rhenish missionaries and their wives. Even today Stellenbosch is a training center of importance. On the ground of the Daughters' Boarding School, in the center of the town, a part of today's university was built.

The picture shows the back of the Daughters' Boarding House including the garden, on the left the school, on the right the residential house. It is a drawing by the missionary W. Leipoldt, around 1887 who was one of the first four missionaries sent out by the Rhenish Mission.

Museum auf der Hardt

Visitor address:

Missionsstraße 9

42285 Wuppertal

Phone: +49 (0)202-89004-152

Postal address:

Rudolfstraße 137

42285 Wuppertal

Opening hours Museum auf der Hardt

Every 1st Sunday of the month 2 pm – 5 pm and on request

Admission 30 minutes before closing time

Other visits by appointment

Admission: 3€/reduced 2€

IBAN: DE45 3506 0190 0009 0909 08

SWIFT/BIC: GENODED1DKD

spenden@vemission.org

0202-89004-195

info@vemission.org

0202-89004-0

presse@vemission.org

0202-89004-135

CRDB BANK PLC / Branch 3319

Account# 0250299692300

Swift code: CORUTZTZ

Bank BNI

Account# 0128002447

Swift code: BNINIDJAMDN

info@vemission.org

presse@vemission.org